Dr. S.H.* is a medical doctor, but she is spreading dangerous false messages about vaccines. In particular, she has been misrepresenting the results of a study of the vaccines against pertussis (whooping cough). Antivaccination activists like to cite scientific research. They want to create the impression that they have done their homework, and that their opinions are scientifically sound. They often claim to be doing “research.” Yet when you look them up in www.pubmed.com, you find that their publication record is thin or nonexistent. Although the antivaccination zealots sometimes read medical journal articles, they typically misunderstand the articles that they discuss. As someone who has edited textbooks and medical journals for a living for more than 25 years, I find their misunderstandings to be irritating. Their work is so full of obvious errors of fact and errors in reasoning that it would never have passed muster at any of the scientific publishing companies for which I have worked. And yet their work is getting plenty of hits on the Internet!

Dr. H.’s basic argument is this: She thinks that it would be better for your baby to catch whooping cough, which is a horrible and sometimes deadly disease, than to be vaccinated against whooping cough. This is what whooping cough is like:

Sometimes, pertussis is even worse than this. Some newborns are not strong enough to cough like this. Instead, they simply stop breathing and die, without warning.

Dr. H. claims that this study by Warfel and coworkers shows that having a natural Bordetella pertussis infection would be better than vaccination for promoting herd immunity. This idea is total nonsense. Whooping cough was once common. It is now rare, thanks to vaccination. Having more natural cases of Bordetella pertussis infection among the population would lead to more illness and more deaths. Better vaccination coverage leads to less illness and fewer deaths.

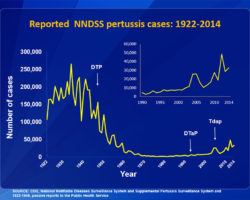

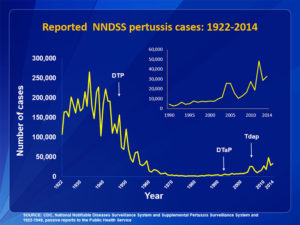

The first vaccine against Bordetella pertussis was introduced in 1940. At the time, roughly 6,000 Americans per year were dying of whooping cough. Roughly 95% of the dead were children. Thanks to the vaccination, the death rate dropped sharply. However, we are still seeing occasional cases of whooping cough, even in highly vaccinated populations. Even the immunity that results from a natural infection lasts for only 4 to 20 years. The protection from vaccination lasts for only about 4 to 12 years. That is why doctors urge people to get booster shots against pertussis. If you have partial immunity to pertussis, you might get only a mild case of the sniffles from a Bordetella pertussis infection. Yet you could pass the bacteria on to someone else, who could get severely ill.

Warfel and coworkers wanted to answer an important question: Is the modern acellular pertussis vaccine less effective than the old-fashioned whole-cell vaccine at preventing the spread of Bordetella pertussis from person to person? Since it would be unthinkable to expose human beings to live Bordetella pertussis, the researchers used baboons as experimental subjects. (Of course, many people have ethical objections to the use of animals, and especially primates, as research subjects.) Like human beings, baboons get a bad cough from a Bordetella pertussis infection.

Warfel and coworkers found that both the acellular vaccine and the whole-cell vaccine were effective for their primary purpose, which is to protect the vaccinated individual from getting sick after exposure to Bordetella pertussis. However, the whole-cell vaccine gave the baboons a little help in clearing the Bordetella pertussis from their upper respiratory tract. The acellular pertussis vaccine did not. It took 21 days for the baboons that received the whole-cell vaccine to clear the Bordetella pertussis from their upper respiratory tract. It took unvaccinated baboons and baboons that received the acellular vaccine about twice as long to clear the bacteria from their upper respiratory tract.

Dr. H. pointed out that the Bordetella pertussis bacteria could not colonize the baboons that were recovering from a recent Bordetella pertussis infection. From that, she concluded that natural infections were better for promoting herd immunity. Yet even the immunity produced by a natural infection declines after a few years. Also, the basic reproduction number of pertussis is 5.5, which means that in a susceptible population, a single natural case of pertussis would tend to lead to an average of 5.5 new cases of pertussis. So if we relied on natural immunity to solve our pertussis problem, we would have huge epidemics of pertussis, as opposed to occasional small outbreaks.

The study by Warfel and coworkers was not about whether to vaccinate against pertussis. It was about which vaccine to use. In the 1990s, Americans switched from the whole-cell vaccine to the acellular vaccine because the whole-cell vaccine sometimes caused children to spike a fever. This fever could sometimes cause a febrile seizure. These seizures were terrifying to the parents, but they do no lasting harm to the child. Some other countries consider this risk of fever to be acceptable because the whole-cell vaccine may be better for stopping the spread of Bordetella pertussis.

Bordetella pertussis is found only in human beings. Thus, we might be able to drive this germ into extinction through vaccination. Once it is extinct, nobody will need to get a pertussis vaccine. Yet to drive pertussis into extinction, we will need a better vaccine, one that provides longer-lasting protection against the carrier state, not just against clinical disease. In the meantime, we need for people to get their children vaccinated and to keep up to date with their pertussis boosters!

*I do not use her real name because I do not like to give people undeserved attention. I explain my reasoning in these two books: