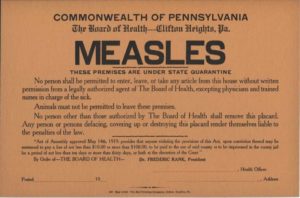

Antivaccine propaganda has been spreading. As a result, so has the measles. Antivaccine zealots are not worried by measles outbreaks. Instead, they want even more people to catch the measles. These antivaxxers believe that measles is a harmless disease that boosts the immune system. (In reality, measles is dangerous mainly because it damages the immune system.) Lately, antivaxxers have been spreading the myth that in the old days, parents would send their children to “measles parties” at the home of a measles patient. In reality, someone from the local board of health would post a quarantine sign on the patient’s home, to prevent any “measles party” from taking place.

Measles Quarantine

A 1941 measles quarantine sign from Clifton Heights, Pennsylvania warned that no one but a doctor or nurse was permitted to enter or leave the house or take anything from the house without written permission from the Board of Health. Anyone who broke that rule or tampered with the sign could be fined up to $100 (which was a lot of money back then) or jailed for up to 30 days. For this reason, “measles parties” would have been rare, if they occurred at all.

My Mother’s Measles

My mother got measles as a kindergartener in Pennsylvania in the 1940s. She does not remember the measles quarantine sign on her apartment; but she was very sick by the time the measles was diagnosed, and she had not yet learned to read. She does remember the quarantine sign from chickenpox, which she got a few years later. While she was sick, none of her friends were allowed to visit. A cousin visited before it was clear that my mother had measles. This cousin then got the measles. My mother also remembers being terribly sick from the measles. While she had the measles, her bedroom was kept very dark to protect her eyes. Her parents knew that measles could cause blindness.

Why Is Measles So Contagious?

Unfortunately, quarantine is not enough to prevent the spread of measles. That’s because at first, a case of measles looks and feels exactly like a common cold. It makes the person cough. Each cough produces a spray of droplets that can carry the virus to other people. You could catch the measles from simply being in a room where an infected person had coughed two hours earlier. Measles is contagious for about four days before the rash appears and the diagnosis of measles becomes obvious. So even though measles patients were quarantined, they were often quarantined too late to keep the disease from spreading. For this reason, nearly everyone who was born before 1957 eventually got the measles.

Measles Damages the Immune System

An ordinary cold runs its course in about a week, as the immune system learns how to make antibodies to that strain of cold virus. But instead of getting better at that point, someone with measles starts to get much sicker. That’s because the measles virus infects some of the cells of the immune system. Instead of killing the measles virus, many of those cells make many new copies of the virus and then die. In other words, the immune system is badly damaged while it is making the measles infection worse. The lingering effects of this damage can last for 2 years.

The Measles Vaccine

I was lucky. As a child in the early 1960s, I was among the first wave of children to be vaccinated against measles. One of our neighbors got measles just before the vaccine came out. I remember how relieved my mother was that we had not been at that girl’s house while she was contagious and how grateful my mother was for the vaccine. In 1971, the measles vaccine was combined into a triple vaccine that immunizes children against measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR). Thanks to the heavy use of this cheap, effective, and remarkably safe vaccine, the United States was declared free of measles in 2000. Unfortunately, measles has not yet been eradicated worldwide, so we still see outbreaks that result from imported cases.

Controlling Measles Outbreaks

Today, a measles outbreak is a public health emergency. Measles may spread like the common cold, but it suppresses the immune system like HIV. For this reason, most of the deaths due to measles are due to secondary infections, such as pneumonia. Even with the best of modern medical care, measles kills one or two out of every thousand patients. The death rate is much higher among people with suppressed immunity, including cancer patients. Up to a quarter of those people may die of measles.

Today, when a measles outbreak occurs, public health authorities race to find and help everyone who may have been exposed. If nonimmune people can be found within 72 hours of exposure to measles, they may be given a dose of the MMR vaccine. Vaccination during that time period may prevent the disease or at least weaken it. If an unvaccinated person cannot be found within 72 hours or is pregnant, is too young for vaccination, or has a suppressed immune system, they can be given a dose of immune globulin instead. Immune globulin is a dose of antibodies from human blood donors. It can be given up to 6 days after exposure. Exposed people who show signs of illness are quarantined, to keep them from spreading the disease to anyone else. During a measles outbreak, children who have not been or cannot be vaccinated may be banned from public school or day care facilities.

Wipe Out Measles, Don’t Spread It!

So “measles parties” are a myth. They would even be a crime. The MMR vaccine is cheap, and it is safe and effective when used as directed. However, it is a “live” vaccine and thus cannot be given to pregnant women, infants, or people with a damaged immune system. To protect them, we need to make sure that practically everyone else is immunized. If we vaccinate enough people worldwide, measles will go extinct. After a vaccine-preventable disease is eradicated, we will not need to vaccinate anyone else against it. Meanwhile, antivaxxers pose a serious threat to public health. They are keeping the vaccination rate low enough to allow diseases to spread, and they congregate in communities and networks that make it easier for diseases to spread.